My Books

Praise for How to Write, Tools for the Craft

“it looks an excellent guide, particularly for university students – by no means only those studying language of course – and we hope tutors will make sure time and attention are given to it.” Books Ireland Sept 1998 “The author leads us through definitions, distinctions and structures in an accessible, reader-friendly manner, using prose that is inviting and lively… Whether the purpose is learning how to write oneself or how to teach others, this book is an excellent guide and resource.” Ireland on Sunday Sept 1998

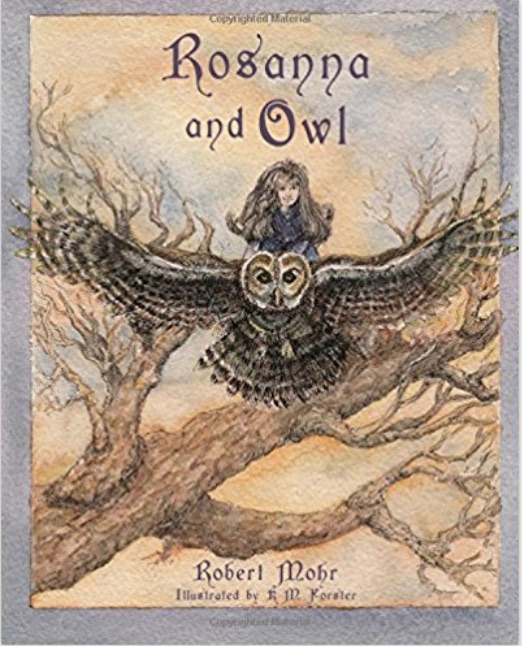

Praise for Rosanna and Owl

Maya, reader age 10:

I have a lot of books on my shelves but this one has become my absolute favourite. Rosanna and Owl brought me on a fascinating, magical adventure to the most special places in their dream-like world. The amazing pictures helped me see into their beautiful world and travel there with them.

Peter Weltner:

Long ago, the poet Ezra Pound remarked about stories like those preserved and re-imagined in Ovid’s Metamorphoses that he once knew a woman who had been a tree. (He was thinking about his friend, the poet Hilda Doolittle.) It was how he understood the story of Daphne changed into a tree to be saved from a god’s ravishment. What metamorphosis meant to him was an expression through ancient myths of human communion, even unity with the natural world in his own day.

Childhood, if a child is lucky, is a mythic world. Woods, steams, wild creatures, meadows, flowers: all these and much more would seem to be one with the child and the child with them.

Children love to listen to and tell stories, and the best of them are about change, about the mysterious mutability and transformations things, animate and inanimate, seem to undergo when experienced through the eyes of a child. Or, in this instance, with the guidance of Owl.

Perhaps this sense of wonder is harder for children now, when so much about the world, not just in cities, seems fraught with danger, too unsafe to wander in and explore or when so much of childhood has been turned over to machines and technique. We are all, not just children, at risk of losing imagination in an electronic world. But Robert Mohr’s Rosanna and Owl would restore it.

It begins, as stories like it must, with discord, in this instance between two of Rosanna’s friends, Jenny and Rachel. In a way, each is one side of Rosanna herself. To reconcile them is to find that reconciliation in herself, but that is less easy than it might appear because of the difference between them. The miracle of her journey is learning that she does have to choose.

Her instructor is Owl, fulfilling owls’ iconic role. Of course, part of that journey is to change, to become bigger or smaller, to enter into the being of others. Rosanna dances in a magic fire circle in a forest. She roams through a meadow filled with flowers and pollinating bees and grows so small observing a flower that its stalk appears high as a pine tree. She is swallowed by Otter, becomes Otter, a creature of dance and laughter and conviviality. She watches Panther save a fawn that swiftly turns into a yearling and so sees a “pure wild heart”

not only saving a life but bringing it into its growth, the older being Rosanna is also more slowly becoming. She meets, in a whitehorn tree, which she enters as well, remarkable, almost Merlin-like figures, one of whom wraps her in a blue gown, Rosanna as sky and tree perhaps. But it is Coyote who teaches her she has to choose between her two different friends no more than she has to choose between two different sides of herself.

The last encounter Rosanna experiences is with Drum. And who is Drum? Heartbeat, the rhythm of things, the pulse of imagination. This is an understanding Rosanna receives which both is and is not wisdom. It is not wisdom because it offers no neat summarization of things in some kind of pity, abstracted meaning, in some easy phrase or verbal summation of what her experiences have been about. It is wisdom because it leaves open, for the rest of her life, the possibility of more meetings with Owl, more metamorphoses, more rhythms, the pulse of being that underlies it all. Her journey goes on as does the book, in its ending, promise more.

Rosanna and Owl is a many-layered book, as entrancing, I would think, to an adult as to a child. It is restorative, a book about a child entering a world much of late modernist childhood has lost, a fable of transformation, a book of changes.

The illustrations for it by Kathleen Forster are superb, as remarkable in the way they adapt a style a hundred years and more old and make it new and fresh and telling as the words do the received figures of legend and fairy tales, for example. Her wondrous dragonfly on page 15, for one striking example, revives an imagery one might have thought lost, as so much of this heartwarming book, word and pictures, does with its understandings of what to grow up feels and looks like, for which no less than a mythic retelling suffices.